Authors:

Published:

This is a guest blog post by our summer fellow Miglena Minkova.

Last week at LIL, I had the pleasure of running a pilot of git physical, the first part of a series of workshops aimed at introducing git to artists and designers through creative challenges. In this workshop I focused on covering the basics: three-tree architecture, simple git workflow, and commands (add, commit, push). These lessons were fairly standard but contained a twist: The whole thing was completely analogue!

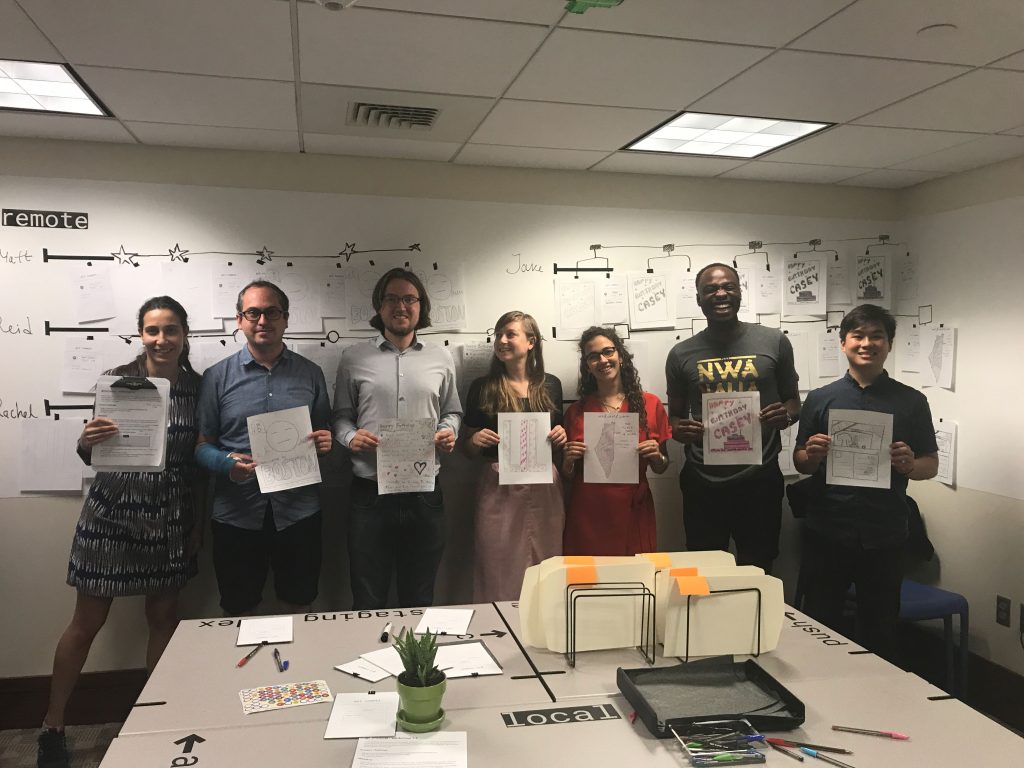

The participants, a diverse group of fellows and interns, engaged in a simplified version control exercise. Each participant was tasked with designing a postcard about their summer at LIL. Following basic git workflow, they took their designs from the working directory, through the staging index, to the version database, and to the remote repository where they displayed them. In the process they “pushed” five versions of their postcard design, each accompanied by a commit note. Working in this way allowed them to experience the workflow in a familiar setting and learn the basics in an interactive and social environment. By the end of the workshop everyone had ideas on how to implement git in their work and was eager to learn more.

Timelapse gif by Doyung Lee (doyunglee.github.io)

Not to mention some top-notch artwork was created.

The workshop was followed by a short debriefing session and Q&A.

Check GitHub for more info.

Alongside this overview, I want to share some of the thinking that went behind the scenes.

Starting with some background. Artists and designers perform version control in their work but in a much different way than developers do with git. They often use error-prone strategies to track document changes such as saving files in multiple places using obscure file naming conventions, working in large master files, or relying on in-built software features. At best these strategies result in inconsistencies, duplication and a large disc storage, and at worst, irreversible mistakes, loss of work, and multiple conflicting documents. Despite experiencing some of the same problems as developers, artists and designers are largely unfamiliar with git (exceptions exist).

The impetus for teaching artists and designers git was my personal experience with it. I had not been formally introduced to the concept of version control or git through my studies, nor my work. I discovered git during the final year of my MLIS degree when I worked with an artist to create a modular open source digital edition of an artist’s book. This project helped me see git as an ubiquitous tool with versatile application across multiple contexts and practices, the common denominator of which is making, editing, and sharing digital documents.

I realized that I was faced with a challenge: How do I get artists and designers excited about learning git?

I used my experience as a design educated digital librarian to create relatable content and tailor delivery to the specific characteristics of the audience: highly visual, creative, and non-technical.

Why create another git workshop? There are, after all, plenty of good quality learning resources out there and I have no intention of reinventing the wheel or competing with existing learning resources. However, I have noticed some gaps that I wanted to address through my workshop.

First of all, I wanted to focus on accessibility and have everyone start on equal ground with no prior knowledge or technical skills required. Even the simplest beginner level tutorials and training materials rely heavily on technology and the CLI (Command Line Interface) as a way of introducing new concepts. Notoriously intimidating for non-technical folk, the CLI seems inevitable given the fact that git is a command line tool. The inherent expectation of using technology to teach git means that people need to learn the architecture, terminology, workflow, commands, and the CLI all at the same time. This seems ambitious and a tad unrealistic for an audience of artists and designers.

I decided to put the technology on hold and combine several pedagogies to leverage learning: active learning, learning through doing, and project-based learning. To contextualize the topic, I embedded elements of the practice of artists and designers by including an open ended creative challenge to serve as a trigger and an end goal. I toyed with different creative challenges using deconstruction, generative design, and surrealist techniques. However this seemed to steer away from the main goal of the workshop. It also made it challenging to narrow down the scope, especially as I realized that no single workflow can embrace the diversity of creative practices. At the end, I chose to focus on versioning a combination of image and text in a single document. This helped to define the learning objectives, and cover only one functionality: the basic git workflow.

I considered it important to introduce concepts gradually in a familiar setting using analogue means to visualize black-box concepts and processes. I wanted to employ abstraction to present the git workflow in a tangible, easily digestible, and memorable way. To achieve this the physical environment and set up was crucial for the delivery of the learning objectives. In terms of designing the workspace, I assigned and labelled different areas of the space to represent the components of git’s architecture. I made use of directional arrows to illustrate the workflow sequence alongside the commands that needed to be executed and used a “remote” as a way of displaying each version on a timeline. Low-tech or no-tech solution such as carbon paper were used to make multiple copies. It took several experiments to get the sketchpad layering right, especially as I did not want to introduce manual redundancies that do little justice to git.

Thinking over the audience interaction, I had considered role play and collaboration. However these modes did not enable each participant to go through the whole workflow and fell short of addressing the learning objectives. Instead I provided each participant with initial instructions to guide them through the basic git workflow and repeat it over and over again using their own design work. The workshop was followed with debriefing which articulated the specific benefits for artists and designers, outlined use cases depending on the type of work they produce, and featured some existing examples of artwork done using git. This was to emphasize that the workshop did not offer a one-size fits all solution, but rather a tool that artists and designers can experiment with and adopt in many different ways in their work.

I want to thank Becky and Casey for their editing work.

Going forward, I am planning to develop a series of workshops introducing other git functionality such as basic merging and branching, diff-ing, and more, and tag a lab exercise to each of them. By providing multiple ways of processing the same information I am hoping that participants will successfully connect the workshop experience and git practice.