Published:

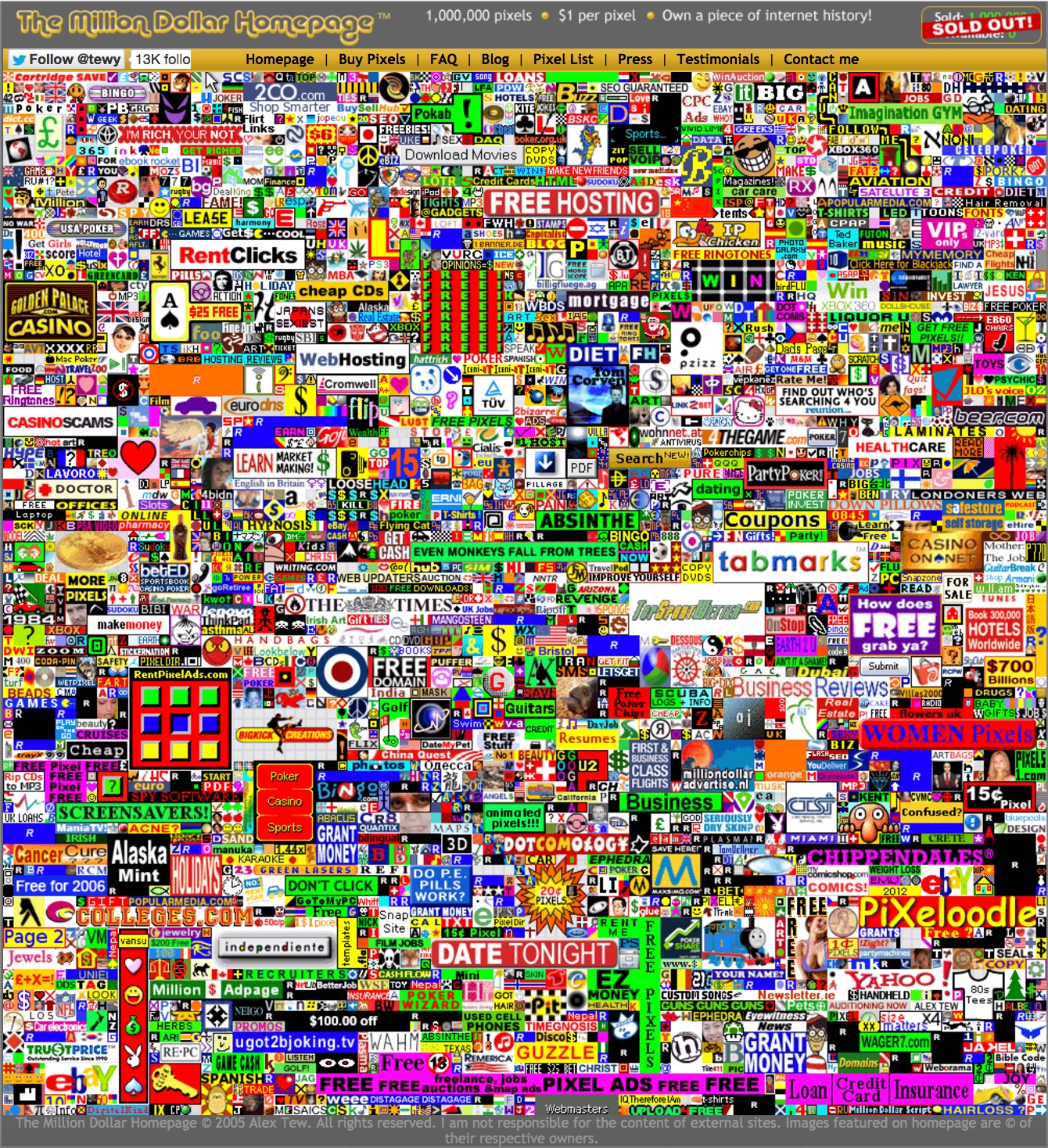

In 2005, British student Alex Tew had a million-dollar idea. He launched www.MillionDollarHomepage.com, a website that presented initial visitors with nothing but a 1000×1000 canvas of blank pixels. At the cost of $1/pixel, visitors could permanently claim 10×10 blocks of pixels and populate them however they’d like. Pixel blocks could also be embedded with URLs and tooltip text of the buyer’s choosing.

The site took off, raising a total of $1,037,100 (the last 1,000 pixels were auctioned off for $38,100). Its customers and content demonstrate a massive range of variation, from individuals bragging about their disposable income to payday loan companies and media promoters. Some purchased minimal 10×10 blocks, while others strung together thousands of pixels to create detailed graphics. The biggest graphic on the page, a chain of pixel blocks purchased by a seemingly defunct domain called “pixellance.com”, contains $10,800 worth of pixels.

The largest graphic on the Million Dollar Homepage, an advertisement for www.pixellance.com

The largest graphic on the Million Dollar Homepage, an advertisement for www.pixellance.com

While most of the graphical elements on the Million Dollar Homepage are promotional in nature, it seems safe to say that the buying craze was motivated by a deeper fixation on the site’s perceived importance as a digital artifact. A banner at the top of the page reads “Own a Piece of Internet History,” a fair claim given the coverage that it received in the blogosphere and in the popular press. To buy a block of pixels was, in theory, to leave one’s mark on a collective accomplishment reflective of the internet’s enormous power to connect people and generate value.

But to what extent has this history been preserved? Does the Million Dollar Homepage represent a robust digital artifact 12 years after its creation, or has it fallen prey to the ephemerality common to internet content? Have the forces of link rot and administrative neglect rendered it a shell of its former self?

The Site

On the surface, there is little amiss with www.MillionDollarHomepage.com. Its landing page retains its early 2000’s styling, save for an embedded twitter link in the upper left corner. The (now full) pixel canvas remains intact, saturated with the eye-melting color palettes of an earlier internet era. Overall, the site’s landing page gives the impression of having been frozen at the time of its completion.

A screenshot of the Million Dollar Homepage captured in July of 2017

A screenshot of the Million Dollar Homepage captured in July of 2017

However, efforts to access the other pages linked on the site’s navigation bar return unformatted 404 messages. The “contact me” link redirects to the creator’s Twitter page. It seems that the site has been stripped of its functional components, leaving little but the content of the pixel canvas itself.

Still, the canvas remains a largely intact record of the aesthetics and commercialization patterns of the internet circa 2005. It is populated by pixelated representations of clunky fonts, advertisements for sketchy looking internet gambling sites, and promises of risqué images. Many of the pixel blocks bear a familial resemblance to today’s clickbait banner ads, with scantily clothed models and promises of free goods and content. Of course, this eye-catching pixel art serves a specific purpose: to get the user to click, redirecting to a site of the buyer’s choosing. What happens when we do?

The Links

Internet links are not always permanent. As pages are deleted or renamed, backends are restructured, and domain namespaces change hands, previously reachable content and resources can be replaced by 404 pages. This “link rot” is the target of the Library Innovation Lab’s Perma.cc project, which allows individuals and institutions to create archived snapshots of webpages hosted at a trustable, static URLs.

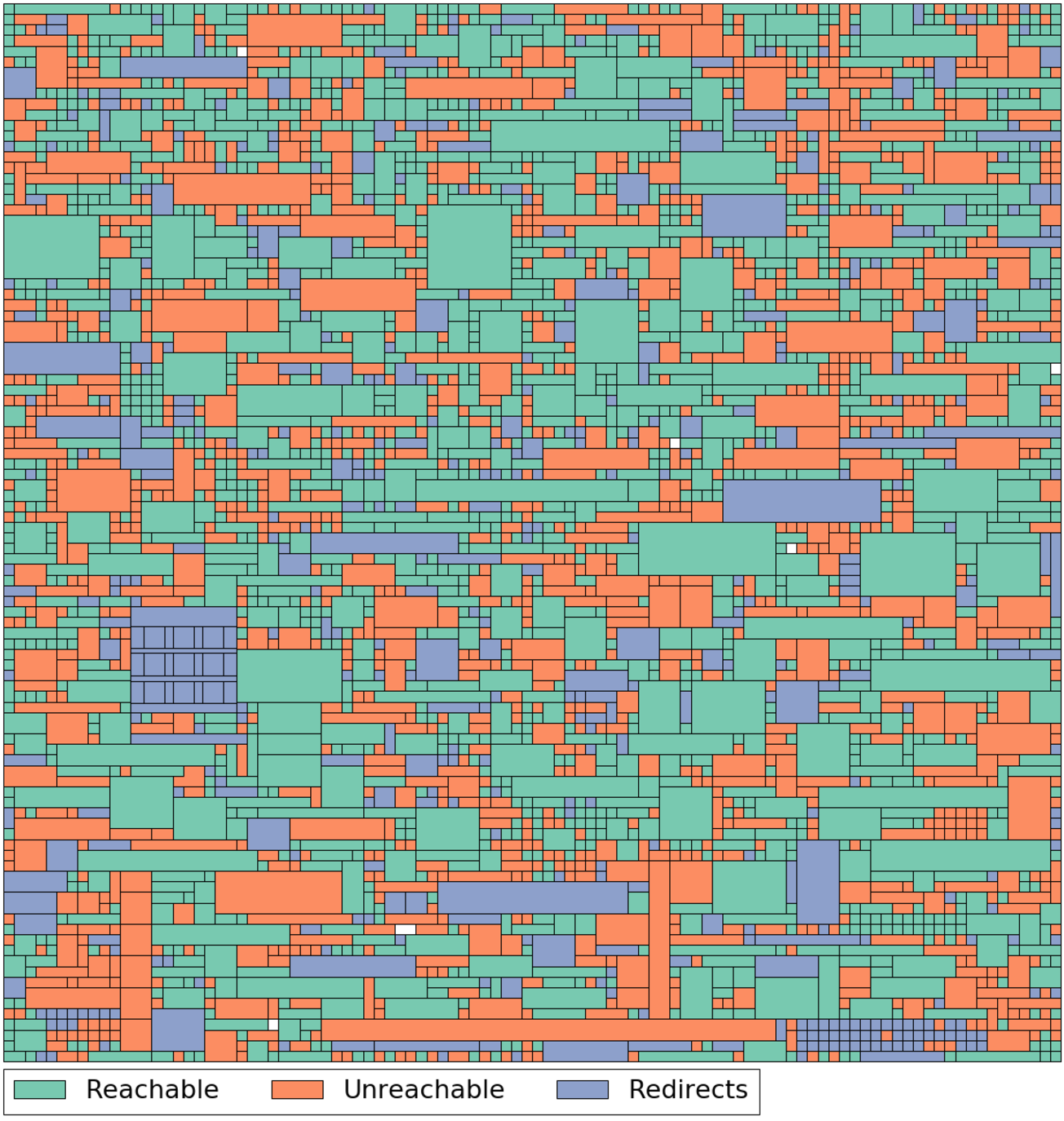

Over the decade or so since the Million Dollar Homepage sold its last pixel, link rot has ravaged the site’s embedded links. Of the 2,816 links that embedded on the page (accounting for a total of 999,400 pixels), 547 are entirely unreachable at this time. A further 489 redirect to a different domain or to a domain resale portal, leaving 1,780 reachable links. Most of the domains to which these links correspond are for sale or devoid of content.

A visualization of link rot in the Million Dollar Homepage. Pixel blocks shaded in red link to unreachable or entirely empty pages, blocks shaded in blue link to domain redirects, and blocks shaded in green are reachable (but are often for sale or have limited content) [Note: this image replaces a previous image which was not colorblind-safe]

A visualization of link rot in the Million Dollar Homepage. Pixel blocks shaded in red link to unreachable or entirely empty pages, blocks shaded in blue link to domain redirects, and blocks shaded in green are reachable (but are often for sale or have limited content) [Note: this image replaces a previous image which was not colorblind-safe]

The 547 unreachable links are attached to graphical elements that collectively take up 342,000 pixels (face value: $342,000). Redirects account for a further 145,000 pixels (face value: $145,000). While it would take a good deal of manual work to assess the reachable pages for content value, the majority do not seem to reflect their original purpose. Though the Million Dollar Homepage’s pixel canvas exists as a largely intact digital artifact, the vast web of sites which it publicizes has decayed greatly over the course of time.

The decay of the Million Dollar Homepage speaks to a pressing challenge in the field of digital archiving. The meaning of a digital artifact to a viewer or researcher is often dependent on the accessibility of other digital artifacts with which it is linked or otherwise networked — a troubling proposition given the inherent dynamism of internet links and addresses. The process of archiving a digital object does not, therefore, necessarily end with the object itself.

What, then, is to be done about the Million Dollar Homepage? While it has clear value as an example of the internet’s ever-evolving culture, emergent potential, and sheer bizarreness, the site reveals itself to be little more than an empty directory upon closer inspection. For the full potential of the Million Dollar Homepage as an artifact to be realized, the web of sites which it catalogues would optimally need to be restored as it existed when the pixels were sold. Given the existence of powerful and widely accessible tools such as the Wayback machine, this kind of restorative curation may well be within reach.